Thursday, August 31, 2006

Orthodox Without a Cause

Well, there's that bit about how the kids might grow up to be Democrats, I guess.

What the hell is a moderate?

Perhaps most predominantly, self-described moderates see themselves as free thinkers, unbound by a political party and its dogmatic platform. Is a moderate anyone who devises opinions on individual issues independent of a party? That makes me a moderate, which is like saying Liberace was on the fence about his sexuality. No one with a brain agrees entirely with one party's platform.

Are moderates people with both "left" and "right" views? I'm one of those, too, then, to a minor extent. (Don't get me started on immigration policy.)

Does a moderate look at what Democrats say, look at what Republicans say, and choose to agree with one party half the time and the other party the other half? Or does he hold an opinion on each issue that's a square compromise of both parties' platforms? Is that even possible?

Along those lines, can we use "moderate" and "centrist" interchangibly? Of course I would argue that the political spectrum is in fact a political Cartesian plane or even a three-dimensional (or eight-dimensional) political sphere, so there is no such thing as a center position, thus no such thing as a centrist. So I'll ask this, too: What the hell is a centrist?

Maybe "moderate" has been confused with "willing to work toward bipartisanship." Somehow the ability to compromise has been construed into its own set of political beliefs.

Or maybe moderates just, more often than not, adhere to inoffensive beliefs. That's why everyone wants to pretend to be one.

Though I don't have any substantial evidence to support my hunch, I sometimes feel that moderates go out of their way to be moderate; they enjoy moderation for moderation's sake. They might agree with a more radically-leaning view at first, but, just to be a good sport, they give that cozy middle a test drive instead.

The biggest problem with moderatism, though, is that, rather than breaking down the partisanism and devisiveness of the extremes, it simply accepts that there are two sides to every story, and that both sides probably have some merit. What this attitude fails to address is that seeing the world as a dichotomous polarity is both inaccurate and ineffecient. Instead of refusing to recognize the value of radicalism, it validates it by sitting smugly in the middle and pretending to satisfy both sides. It seems a little counter-productive.

Ultimately the word "moderate" is substantively meaningless and usually an attractive cover for being apolitical, nonconfrontational, or a panderer.

Feminist Blogs

Wednesday, August 30, 2006

To be fair...

Whenever I get into a flame war I always find myself doing a little bit of a walk back when I’m done. Let’s just say I can get carried away and that’s not good. So in that spirit let me delve a little deeper into the whole “inherent moral obligation” thing.

An inherent moral obligation has to arise from an inherent property of that thing. The test for inherency seems straightforward – is it conceivable for the object to exist without this property? If so than it’s not inherent – but in reality it’s not all that clear when you’re dealing with something which is not defined very well.

Definitions! Almost all flame-wars end up on this topic. I try to take a strongly relativistic view of definitions: There is no “right” definition for a word; there’s only “right in context”. The context I usually adopt is “what helps you think about things more clearly”. This is why for example I reject both “War on terror” and “islamofascism”.

Ok, enough of that. The question before us was “how do you define a species”. Short answer: it’s hard. I’ll link to dues-ex-wiki. What do you guys think?

Sunday, August 27, 2006

Hating On Unions

When teachers and their employers are at loggerheads over salaries and working conditions, should they be able to strike, thereby closing the schools?I mean, that's the point of having a union, right? You're not left with much when you take away the credible threat of a strike.

You heard the same sort of union skepticism when the public transit workers were striking in New York City last year. There was lots of, "Oh, I support unions in general, but I really don't think they should be able to strike when it's so inconvenient for other people," and , "But why do they have to strike right now?"

If you want people to work, you either meet their demands, or you come to terms with the fact that they're not going to do it. What's the alternative supposed to be?

Saturday, August 26, 2006

The problem with "unbaised" media

Two journalists explain their professionWashington Post reporter Jonathan Weisman participated in an August 25 online discussion on the newspaper's website:

West Coast: Dick Cheney said he was stuck with the grave decision of whether to shoot down the flight that crashed in Pennsylvania or not. The recently released NORAD tapes confirm that the government first knew of the flight one minute before it went down. Is Cheney lying, again, or was he thinking very fast that day, with his drama unfolding within 60 seconds? I've yet to read anywhere that Cheney has been queried about his story. THANKS.

Jonathan Weisman: If I can get him on the phone, I will query him. Cheney's statements present a quandary for us reporters. Sometimes we write them up and are accused of being White House stenographers and stooges for repeating them. Then if we don't write them up, we are accused of being complicit for covering them up. So, all you folks on the left, what'll it be? Complicity or stenography?

We can't speak for all the "folks on the left," but we suspect most of them would choose "Option C: Journalism."

Indeed, several participants in the online discussion made exactly that point. As one put it: "[R]esearch and intelligent questions based on said research that makes up 'Reporting'. Retyping statements without research is 'Stenography'. Avoiding asking tough questions because it makes your original stenography look really, really bad is 'Complicity'." Weisman, showing nothing but contempt for his readers -- and, though it seems he didn't realize it, for his profession -- responded with a series of churlish comments like "Please apply for my job" and "Sometimes, you folks really drive us nuts."

We can assure Mr. Weisman that the feeling is mutual.

Is it any wonder that the media has done such a poor job of educating Americans? They can't even decide if reporting the facts is more important than avoiding illogical criticism! If reporting the news “with a point of view”* is the price we pay for avoiding journalist-retards like this guy, it’s a small price to pay.

*A description employed by Fox news.

Update: Berkeley-local Brad Delong asks the same question.Friday, August 25, 2006

Balkinization

The upshot was supposed to be that if you're a Scalian sort of originalist, you're commited to the proposition that schools today would not be prohibited from teaching the theory of spontaneous generation, even though that theory was disproved in 1862. After all, the Founding Fathers, during the ratification process, would not have considered the theory of spontaneous generation to be prohibited by the hypothetical Constitution.

Anyway, it's a very well-written article, and will be of special interest to those who, like me, very much dislike the tendency in most discussions for underlying principles to be ignored in favor of more superficial - and often extrinsic - considerations.

Thursday, August 24, 2006

Deciding to keep rainbow trout

We give ourselves altogether too much credit in our dealings with other species. Even the power over nature that domestication supposedly represents is overstated. It takes two to perform that particular dance, after all, and plenty of plants and animals have elected to sit it out. Try as they might, people have never been able to domesticate the oak tree, whose highly nutritious acorns remain far too bitter for humans to eat. Evidently the oak has such a satisfactory arrangement with the squirrel—which obligingly forgets where it has buried every fourth acorn or so (admittedly, the estimate is Beatrix Potter’s)—that the tree has never needed to enter into any kind of formal arrangement with us.I don’t like this metaphor; mostly because it embodies all the wrong instincts about how we should think of the environment. The bargain isn't equal. For one thing the selection pressure the plants exerts on man is not nearly as large as the pressure man exerts on the plant. Further, man’s long lifespan ensures that we respond to that pressure far slower than any domesticated plant (which ussually can yield a new generation each year). Representing domestication as a co-equal partnership is unspeak of the silliest kind.

If I had to propose my own metaphor I would say that domestication is something like a business arrangement: an exploitive one. After all, the apple and the potato didn’t choose to join us on our travels: we forced them to. We cleared fields of unsavory potatoes, replacing them with ones we could more efficiently exploit. And the second we found a more flavorful exploitable potato plant, we uproot our existing business partner and replanted again. Sure, we assist the plant in reproducing – but even Walmart pays it's employees enough to live. That doesn't mean they're getting a fair deal.

Of course, my metaphor has problems too. But it’s just as valid as Pollan’s. The reason I bother is to show that both metaphors make the same mistake: both assign independent moral worth to a plant.

I want to be clear. I’m not saying we have no moral obligation to preserve plants and animals. I’m just saying that those moral obligations are not inherient obligations. For example, we have a moral obligation to leave our children a livable world. Because of that we are obliged to preserve the world’s oceans and wildlife. But we certainly don’t *owe* the rainbow trout a place to live. If we decide that maintaining rainbow trout are beneficial to our long-term interests than we keep them, if not, too bad for rainbow trout.

The reason I take this position is because I think the concept of inherent moral worth of plant (and animal) species is just unworkable. We might take great lengths to prevent the native plants of Hawaii from being killed off by non-native species, but even those native species got there by invading the island and destroying the plants that came before. Similarly the cane toad might be annoying today but if – over the course of millions of years - it were to diverge into hundred of separate species found only in Australia, I think we’d rethink our current policy of trying to kill them off.

Now, I assume this is going to set off all kinds of bells and whistles in the heads of some of you. “But Tom! If the decision to preserve wildlife is based only on what it’s worth to people, won’t people make shortsighted decisions?” Why yes. Yes, they might. But the solution to that problem is to get people to make not make short-sighted decisions, not to pretend that god will get mad at us if we let Imperata cylindrical die out. Trying to fix bad judgment calls by inventing procedural grounds upon which to push your favored outcome is not a good way to ensure logical conclusions.

Update: Removing possibly over-the-top reference to slavery.

Wednesday, August 23, 2006

Clearly, I Must Be Missing Something

The probability of, say, a nuclear terrorist attack might be tiny but the consequences, the “payoff” as it were, would be huge. It is expectation, not probability, that should determine policy towards terrorism."Expectation", here, means "probability times the payoff".

I don't get what the big deal is supposed to be. Of course you need to consider both the probability and the payoff of the evaluated events, but dying in the blast of a nuclear bomb isn't any worse than dying in your bathtub. The whole point of the bathtub drowning comparisons is that the payoff is just as great - you're dead one way or the other - but the precautionary measures taken in case of terrorism are vastly out of proportion to the probability differential between terrorism deaths and bathtub drownings.

What am I missing?

Tuesday, August 22, 2006

Polls Rock

The usual refrain is that following polls inhibits creativity and a willingness to buck public opinion when it's best for the Country. World War II wasn't popular when we got into it, etc.

But that seems to overly confuse competency with direction. Direction NEEDS to be at least partially poll-driven. What is the most important issue facing the Nation? What makes you happy? What makes you sad? Aren't these just the basic metrics that every President needs to have at his fingertips? To do otherwise would be like running a business without a balance sheet. You'd be living in your own vacuum, where wrong decisions are magnified by the lack of a corrective, and there is no mechanism to pull away from a bad road. Once direction is decided, with the aid of polls, it's solely the President's job to decide HOW and WHEN to fix the problem -- and that's his real job.

In conclusion, polls rock.

What's Wrong with America

One article in the September issue examines three case studies of "A+" students, one from a home school, another from a private school, and the third from--and this is supposed to be shocking to the reader--a plain-old public school! Anyhow, the introductory paragraph rattles off a litany of indicators that America's schools are failing: a quarter of students don't finish high school, only a third of eighth graders score at grade level in math and reading, etc.

Naturally these startling--startling!--figures aren't compared to statistics from previous generations' students (thanks, Paul), but rest assured that "[w]hen it comes to education, our children are in trouble." Assuming we're worse off now that twenty years ago (which I doubt), whom should we blame for our crippling moral failure as a nation? Lack of funding from federal and state governments? Increased grade-level standards and AYPs? Atheists and homosexuals? No, silly. Teachers!

There are plenty of reasons for all that failure--from stultifying school bureaucracy to reform-resistant teachers unions to poorly qualified teachers.Does anyone actually believe this? Are morons across this great nation actually falling for the witch-huntery that the media levy against educators? Do people actually think that waves of unqualified idiots are plucked from local rehab clinics and prison cells to teach American children? Where did all these horrible teachers come from?

In an unrelated story, as reported by the Wall Street Journal this morning (this also arrives into my house under my boyfriend's name--this time it's his dad's fault), bears are bothering people in their homes and recreational areas more than they used to. (They are?) Of course this troubling conflict is because bears are getting too bold, not because humans continue to encroach upon bears' habitat. Uh, yeah.

If I were queen of America I'd pass a law that if you publish supposedly alarming statistics then you have to (a) offer comparative statistics (from either another geographic area or time period, just so we know why we should be pissed off) and (b) actually analyze the causes in a fair, realistic way.

If American schools are failing to do anything it's teaching people how to examine causes when citing an effect.

Sunday, August 20, 2006

What Our Op-Ed Pages Isn't Teaching Us

In our better private universities and flagship state schools today, it's hard to find a student who graduated from high school with much lower than a 3.5 GPA, and not uncommon to find students whose GPAs were 4.0 or higher. They somehow got these suspect grades without having read much. Or if they did read, they've given it up. And it shows -- in their writing and even in their conversation.How does he know this? Well, you see, he has "a list of everyday words" that have stumped college students he's talked to. Sounds open-and-shut to me!

As it turns out, Skube's thinking has three big problems. First, he's got a strange definition of "everyday"; words on his list include "impetus" and "pith", both of which I have gone many, many consecutive days without coming across. Second, apparently a word need only be unknown to a single college student to end up on the dreaded Skube Register.

Third, and worst of all, Skube gives no indication - and appears to have no clue - as to whether the undergraduates of today are any worse off than the undergraduates of the past. In fact, he seems to assume that lots of people are unfamiliar with the words in question; of the 9 "everyday words" he identifies as being too advanced for college students, he defines 6 for his readers.

I'm going to start keeping a list of college instructors I find who collect anecdotes, gripe about them, and then confuse the whole thing with science.

Friday, August 18, 2006

A Hard-Right Question

It seems to me that the proposition that Congressional judgments about the proper scope of surveillance (even surveillance aimed at catching foreign terrorists) prevail over Presidential judgments is hardly a "hard-left" view. If the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act prohibits the NSA program (my reading is that it does), the Authorization for the Use of Military Force doesn't implicitly authorize what FISA forbids (and it's at least quite plausible to say that it doesn't implicitly authorize it), and the Congress has the constitutional power to constrain the President this way (and again it's at least quite plausible to say that it has such a power), then the NSA program is illegal. And even if the program is nonetheless valuable for national security, there are perfectly sensible non-hard-left arguments for concluding that the rule of law should trump even national security concerns (especially if one believes, as I do, that the constraints on the program are statutory and can thus be removed, if necessary, simply by getting Congress to change the law).Now, I know Professor Volokh is all lawyerly and stuff, but aren't there also plenty of "perfectly sensible non-hard-left arguments" against the NSA eavesdropping program that don't have anything to do with "the rule of law"?

For instance, one of my objections to the program is that you shouldn't trust the Executive with the power to monitor the correspondence of citizens without at least moderately adversarial oversight by another entity. This is because you can't trust the Executive to autonomously and reliably hold its own actions to the standards that must be met to justify governmental invasion of an individual's privacy. Is this a "hard-left" position? It seems to me that it's actually a very common view, historically. What, exactly, would be a "hard-left" position on this issue?

Moreover, it's not just the case that the privacy argument is an objection in addition to the rule of law argument; one of the purposes of the law is precisely to protect the right to privacy of the individual. The rule of law argument will, in all cases, depend ultimately on additional, less legal, more strictly ethical, arguments about the actual impact of the laws in question. I'm therefore wary of the implication (even if made only by omission) that those other, more normative arguments are necessarily "hard-left".

Really, I think what we're really dealing with is a hard-right question, namely, Should the President be allowed to spy on American citizens without a warrant?

I've had it with these motherfucking snakes!

This is not politically relevent, except as an illustration of Hollywood's mysterious magic powers.

Bad omen

Wednesday, August 16, 2006

International Blah

Conservatives are retarded, as usual. They only hate International Law in foreign affairs now because it’s getting in Bush’s way. Clearly there’s an argument against using it in American jurisprudence.. as Justices Kennedy and Breyer have hinted at doing. But even there, it’s mostly just being used as a helpful moral reference point to ponder.. and all American common law is taken wholesale from the English, after all.

All that being said, I’m going to critique Liberals who use it now, because I fundamentally care about what they think, whereas I think Republicans are retarded.

1. It’s not very Democratic

Treaties – the major source of International Law – are only weakly Democratic at the best of times. They are negotiated and agreed to by the Executive branch, and usually rubber-stamped by Congress. They reflect – not Domestic political concerns – but the give and take of international negotiations. Take, for example, the League of Nations. It reflects not a democratic mandate to Wilson, but protracted international struggles. In addition, nations that ratify these laws often don’t require much in the way of democratic approval, thus robbing the agreements of much of their ‘Morality of the World’ argument.

For example, the same process that led to the WTO and IMF – widely reviled among Liberals – also lead to the Geneva Conventions. The trend is clearly towards centralization and non-democratic agreements.

The same process that led the US to sign the Geneva Convention could just as easily get rid of it. The President takes us out of it, and the Republican-led Congress approves. That’s as Democratic as it gets with these things. Does that deprive it of moral weight?

2. They barely make sense

Some Conventions are genuinely widespread, like the first Geneva Conventions. But the rest of ‘International Law’ is patchwork.. confused.. old. The International Criminal Court, for example, has only 14 signatories, pretty much all of them EU. Does it hold any authority over the US? Should it? How about the Treaties against Mines? Almost everyone has signed that one, excepting the US and a few evil nations. Does it hold any moral weight? Or legal weight to be considered?

3. It gives up too much in Sovereignity

There are some Liberals who seem to want to use International Law as a trump card over US objectives overseas and at home. That’s a dangerous road to walk. The International Criminal Court, for example, would give a lot of power to people completely unaccountable to our democratic processes… same as with other international institutions. That’s not something to enter into lightly. Personally, I don’t trust Europeans – or any other Nation – more then I trust the US. What will I get out of it ceding moral and legal authority to them as a group?

Monday, August 14, 2006

Most. Boring. Story. Ever.

These lights, which are embedded in the roadway and activated by a push button, flash to notify drivers that pedestrians are coming and that they need to stop. On Tuesday morning, the Berkeley Office of Transportation was notified that the light at Parker and Telegraph streets wasn’t working.

“I got an e-mail from Councilmember [Kriss] Worthington himself, indicating that it was not working and I directed it to the electrical crew,” said Tamalyn Bright, Office of Transportation. “We found out that our electrical crew had decided to refer it to Silicon Constellations, an outside contractor.”

When Worthington was informed of the update, he replied, “We are very grateful to Tamalyn for her rapid response.”

George Conklin, nearby Berkeley resident, first noticed the malfunction of the lights on Sunday night and reported it to Worthington.

Economic Social Dislocation Globalization

The present problem with Globalization is that it's only halfway implemented. Lets define Globalization inadequately as the free and frequent movement of stuff across national borders. Globalization with respect to Money is going very well. Capital flows move happily across the world, supported by an impressive international framework. Trade is pretty reasonably free. We've got some stupid restrictions on stuff like agriculture and textiles that amount to a big subsidy to agribusiness and a few politically connected industrial barons.

We don't have free movement of people. Not even close to it. And that's the third big piece of the triforce.

Diligent Economic scientists everywhere have chronicled the economic problems this causes. Essentially, you get dislocations of people that benefit some people (lower-class blue collar Americans) and hurt some people (everyone in Mexico).

I'm wondering more if this creates some problematic social issues. Lets say for a moment that social harmony and understanding of other cultures requires some level of actually mixing and hanging out with them. So while the Middle East is getting, say, a big influx of American culture, goods, and money, it's not spending time with any real Americans, excepting some charged interactions in Iraq. Similarly, while the American Northeast is getting a lot of imported goods, Mexican restaurants, and Japanimation, it's not spending time with any of the cultures associated with it. And, anecdotally, it seems like places in America without a large influx of immigrants are more prone to Xenophobia. Whereas the San Franciscos of the world just open more Thai/Ethopian fusion restaurants.

So I'm wondering this: if you get an infusion of foreign ideas, money, and goods without that socializing level of human cultural contact, you'll get rising indignation and hatred of the interlopers.

A good counterexample would be the American Southwest, where there's been a Latino backlash somewhat. But even there, people seem pretty accepting of Latinos, considering how dramatic the immigration has been and how limited the backlash has been. (Largely to the Economic losers from immigration)

Saturday, August 12, 2006

Lamont vs. The Hawks -- The Hawks vs. Reality

So what are we rejecting? As Chait would say this election serves to “intimidate other hawkish Democrats”. Unlike him I think that’s a good thing. I don’t belong to the school of thought which says that being a hawk – advocating aggressive policy on foreign relations – is equal to being strong on defense. It depends on the situation. Currently, the hawkish position is a weak one and that may be why Democrats are polling higher than Republicans on issues like Iraq and terrorism.

This article lays it out well. During the cold war hawks were probably the purveyors of the most dangerous, most destabilizing, least secure foreign policy in America. Nowadays the same is true though for different reasons. The cold-war hawks were unserious because they didn’t accept the limits imposed by the nuclear stalemate; the current hawks are unserious because they don’t appreciate the limits imposed by modern asymmetrical warfare. Though realities have decreased the usefulness of war, the hawks continue to indulge their emotional predisposition to to solve problems though war, insisting that they have a way to make it work.

Bush assumed he could solve the problem of Al Qaeda by invading Iraq (though to be fair he thought it would solve a whole lot of other problems as well). Rumsfeld assumed could escape the limits of asymmetrical modern warfare by waging blitzkrieg with a tiny ground force. When that didn’t work some hawks suggested putting the State department in charge (what they were supposed to do differently wasn’t even explained). Some are suggesting we “get tough” with Iran or Syria though as of now few of them are brave enough to come out and say what exactly they mean.

In all cases the underlying assumption is the same:

- The pre-war situation was intolerable

- A tolerable situation is achievable

- Therefore there must be some kind of war we can wage that will make the situation tolerable. It’s only a matter of figuring out what war that is. QED

I'll discuss the alternative - standard liberal internationalism - later.

Friday, August 11, 2006

Un Camejo Mejor

The silver lining here is that Camejo has abandoned much of the pretense that his candidacy matters. Either that or he thinks that expressing that we're "free to vote for" him will inspire in us a great sense of civic duty. We're similarly "free to" root for the Celtics at a Bulls-Knicks game. At least he's playing the right sport.

Thursday, August 10, 2006

What Our Children Isn't Learning

Sure enough, as this AP article discusses, many schools are dropping electives for their students:

Havenscourt Middle School in Oakland, Calif., decided to require two class periods of the core subjects for all students. The change left no time for electives and forced the school to drop wood shop, art, music and Spanish. Now, those electives and others are offered before and after school as extras.

Now, depending on the particular elective in question, I might be more or less bothered by its removal from the regular school day. And the article mentions the standard, abstract objections to narrowing the curriculum so severely. What the article fails to mention, however, is a phenomenon that is occurring in some middle schools: the removal of science and history classes to make room for additional math and reading. (I do not know for sure, though I guess, that this phenomenon is somewhat less common in high schools, which, I assume, have more of an eye toward university entrance requirements.) Indeed, the words "science" and "history" do not even appear in the article.

It probably goes without saying why this development is unfortunate - just off the top of my head, much of the reason we teach math and language arts in the first place is that we ultimately want to facilitate the learning of science and history, and one has a hard time imagining why 12-year-olds would care as much about math or reading if they didn't have science or history to apply their skills to - and it's definitely noteworthy, so I'd hope to read more about it in the papers.

Update: Oh man. It's like the world conspires to provide me with convenient illustrations to fill out and expand upon my blog-points:

A comparison of peoples' views in 34 countries finds that the United States ranks near the bottom when it comes to public acceptance of evolution. Only Turkey ranked lower.

Among the factors contributing to America's low score are poor understanding of biology, especially genetics, the politicization of science and the literal interpretation of the Bible by a small but vocal group of American Christians, the researchers say.

"American Protestantism is more fundamentalist than anybody except perhaps the Islamic fundamentalist, which is why Turkey and we are so close," said study co-author Jon Miller of Michigan State University.

...

The study found that over the past 20 years:

- The percentage of U.S. adults who accept evolution declined from 45 to 40 percent.

- The percentage overtly rejecting evolution declined from 48 to 39 percent, however.

- And the percentage of adults who were unsure increased, from 7 to 21 percent.

So while the survey doesn't deal directly with the practice of double-blocking math and English at the expense of science, it is evidence of increasing disregard for science in general in American society.

The liberal instinct might be to blame this all on religious conservatives muddying the waters with quackery like "intelligent design" theory, but we shouldn't neglect entirely the impact of the rise of standardized testing. The emphasis of such tests is almost always predominately - if not exclusively - on math and language arts. Problem is, big chunks of those subjects aren't terribly useful unless you can apply them to science or history. It would be a shame if we managed to boost our kids' math and reading scores only at the net expense of their bag of useful skills.

"It's a cowardly refusal to answer."

HH: Do you want the Democrats to win majorities in the House or the Senate, Martin Peretz?

MP: I'm...I'm appalled by some of the people who would become head of Congressional committees.

HH: Is that a no?

MP: Uh, but I'm also appalled by some of the shenanigans...

HH: But is that...I've got five seconds. Is that a no, Martin Peretz?

MP: It's a cowardly refusal to answer.

HH: (laughing) Okay. We'll carry it on, later. Martin Peretz, thanks.

Ok, when you can't make up your mind over who he wants to win congress, you aren't a liberal. I know that Martin Peretz is a crazy who only gets printed becuase he bought the magazine, but seriously how can people get worked up over the monetary ties of a voluntary advertising ring run by

The insidious plot to accurately study things

The really wondrous thing about the last group is how fervently they reject any kind of social responsibility. I read Hit and Run, the libertarian blog because I get to see people like Jacob Sullum display the wonders of purse ideological reasoning:

USA Today reports with alarm that researchers have found cotinine, a nicotine metabolite, in the urine and hair of babies who live with smokers—even when their parents did not smoke in their presence. It seems components of tobacco smoke cling to smokers and to household surfaces and get picked up by babies who come into contact with these intermediaries, a phenomenon "some doctors are calling 'thirdhand' smoke." Even something as seemingly benign as a mother's hug may be passing along deadly toxins and carcinogens!A person unfamiliar with libertarianism might not predict where this is heading. A regular person might think something like “Ok, babies might be in trouble, we should really study this more” or “Good thing we did this study. I wouldn’t want to accidentally hurt my child or someone elses.” You might think something like that, but apparently, according to Sullum, you’d be missing the point:

Not until the second-to-last paragraph do we get this caveat, courtesy of "Brett Singer, a scientist at California's Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory": "The million-dollar question is: How dangerous is this?...We can't say for sure this is a health hazard."

Notice where the logic of "thirdhand smoke" leads us. Not only are parents who smoke around their children, or in the same house as their children, or even outside that house, guilty of child abuse; anyone who smokes is potentially guilty as well, since the contaminants may be passed along via residue in a room later occupied by children, physical contact with children, or physical contact with some third party who later interacts with children (although that would be "fourthhand smoke," I guess). To err on the side of caution—which is where we always should err when it comes to the welfare of children, of course—everyone should just stop smoking right now. Then there won't be any need to call the cops.As liberal I think personal autonomy is great, but certain personal actions do negatively affect others and this leads to moral obligations. Furthermore, if the negative effect is great enough, I think a valid state interest is created and laws should be passed. Obviously we’d prefer not to, but it’s better than the alternative.

To the libertarians at Hit and Run however, the real problem isn’t sick babies. No, it’s involuntary legal obligations. I think that says it all right there.

You know, if someone was actually trying to ban all smoking based on this Sollum would have half a point. Since that’s not the case it’s pretty clear that he’s just kind of crazy.

Wednesday, August 09, 2006

Rape and incest and abortion, oh my!

My bone to pick today is how frequently rape and incest are used to justify keeping abortion legal. "You don't believe a woman has a right to abort her fetus? Well, what if she was the victim of rape or incest?!" It's the pro-choice camp's analog to the "yo momma" retort. There really isn't a good comeback to that, but nor is it a very good comeback itself.

Very few abortions are prompted by rape and incest. The prevailing estimate attributes about one percent of abortions to R&I.* Because these data are self-reported by the would-be mothers, the number is probably higher; shame and fear most likely cause many victims to keep mum about their true motivations. But even if the number were three or five percent, R&I would still represent a tiny slice of abortions.

So why do pro-choicers cling to rape and incest as their rhetorical side-kick?

First, it's a handy conversation stopper when debating with a pro-lifer. Rape and incest are less funny than cancer and Carrot Top combined, and only a truly dedicated anti-abortion advocate would get tangled in this argumentative net. Pro-choicers can bank on the fact that anyone who thinks that a woman should be forced to give birth to her rapist's baby will look like a raging asshole.

Second, I think it's emotionally and politically difficult for many pro-choicers to admit that they think abortion is okay in any circumstances. No one wants to concede that he thinks it's acceptable for a woman to subject herself to an emotionally scarring and potentially dangerous procedure that also, incidentally, sometimes terminates the existence of a blob of tissue that kinda looks like a real person. Whether or not you think a fetus constitutes a life, it takes a lot of conviction to dismiss abortion as no more serious than trimming a fingernail.

It's uncomfortable to say that, yes, it's better for both the would-be mom and the would-be baby that this pregnancy be ended than that an unwanted child is introduced to this world. It has a socially Darwinian ring to it, even if that's not the pro-choicer's true feelings, and in such an emotionally-charged debate, you can't afford to give your opposition any ground to stand on.

Thus, understandably, pro-choicers fall back on the rape and incest argument, and one percent of abortions are used to justify the other ninety-nine percent.

This debate--any political debate--would progress much more efficiently if everyone argued honestly rather than strategically.

* Coincidentally, about the same proportion of abortions occur in the third trimester as are attributed to R&I. So-called "late-term" abortions are often used by the pro-life camp as an argument against any legally available abortion, so the red-herringry works on both sides.

Tuesday, August 08, 2006

Making Illinois Feel Better About Its Governor's Name

Update: Lamont wins and Lieberman will form a new party with the terrible name "Team Connecticut". Can't say I'm too worked up about his 3rd party run - there's clearly an ego problem, but it's not obvious to me that he doesn't really believe that he's the preferred choice of the voters of Connecticut. Bad for the Democratic party and most brands of liberalism, but it's hard to see why Lieberman can't just say that such problems aren't the unfortunate, but short-term, costs of democracy. We're talking more Ross Perot than Ralph Nader.

Interesting wrinkle - what will Harry Reid do?

Lets bias the press!

It is, first of all, unworkable. We come into this world politically neutral. Soon afterwards, society, friends, parents, teachers, and the rest of the world inflicts a series of unconscious and conscious biases and heuristics onto us. Of course we're politically biased. And those biases inevitably influence article choice, word choice, phrase choice, and selection of facts. As the depiction of the world found in a news article is inevitably incomplete, it will be skewed. Legions of stupid bloggers have found their reason to breathe in the constant cataloging of journalistic deviations from some imagined neutral land.

But who gives a shit? Who cares if a paper or news station is biased? It's a free country. The news can do whatever they like, write whatever they choose. No one has to buy the end result, and increasingly, no one does. I recognize that many people cling to a model of journalism amusingly called 'the fourth estate,' where the news occupies some vital civic function that requires a level of neutrality. Such that the unthinking masses must receive carefully grey news to become proper citizens.

I call bullshit on this. It doesn't matter one bit on a civic level whether or not the news is unbiased. First, it is biased, inevitably. Second, consciously unbiased news is boring, and boring news is easily avoidable. As a tedious assembly of facts in a pyramid, constrained style, it holds no candle to the fiery rhetorical weight and fun wordgames of unconstrained biased writing. Look at England, where London supports masses of fun, free papers with real personality and passion. Somehow, the Polis survives. Third, the current model isn't working. Unbiased papers and stations are fading and dying. If we want any fourth estate at all, we need a new, better model that can compete with the Daily Show and Fox News. Fourth, the idea that consumers will be ill-informed because most get their news from only one source is a fading concept. Younger readers rarely if ever read one outlet -- I probably read nine-ten.

Finally, we can already see what the world will look like once papers and stations feel free to be biased. And it's not bad at all. As in England, we can expect news outlets to divide themselves along a political spectrum, roughly equivalent to the market share of those opinions. As with everything else in american politics, they will cluster around the center, with a few outliers. The resulting outpour of news will be generally the same, with the few disputed political facts sharply visible by the divide between papers and the struggle in the surrounding blogs.

More people will read news because it'll be more interesting -- the Fox News effect. Newspapers will find their true calling by contextualizing the news, repackaging the same facts for consumption. And, most importantly of all, we will no longer waste time and effort critiquing the news for some mythical level of neutrality. The only possible critique will be on the factual correctness of the news, and how it works in the wider political sphere.

Of course, my real goal with all of this is to kill off the horrible, small-minded bloggers that relentlessly look for bias in every headline. But I'll accept a smarter, less hypocritical news sphere as a side bonus.

Monday, August 07, 2006

Saturday, August 05, 2006

Relativism Run Amok

Creationists, after all, are just as sure that they are right about Darwin as evolutionists think themselves to be.Phonics-based instruction is controversial because the data are mixed. Evolution is controversial because some people reject the fundamental premises of scientific inquiry.

Of course, in education, Darwin is just the beginning: Is phonics-based instruction the right or wrong way to teach reading? Should American history be taught in a “traditional” way that focuses on the nation’s great achievements, or is it right to focus on the country’s flaws? What amount of time should students spend studying fine art instead of, say, physics? Is it wrong for a student newspaper to run an article critical of the school’s principal? And so on…

Clearly, when it comes to countless disputes in education, what is truly right or truly wrong is very difficult to know. With that in mind, we must answer the question: Is it better that government impose one idea of what’s right on all children, or that parents be able to seek freely what they think is right for their own kids?

Now, parents can, if they so choose, pull their children out of the public school system and impose upon them any manner of ridiculous notions by sticking them in alternative educational environments. The government, however, has no obligation to subsidize such behavior. This is particularly true in the case of the evolution controversy, as the only reasons to reject evolution are religious.

But really, it's the relativism that's the problem - you just can't take it seriously. I, after all, am just as sure that I am right about school choice as libertarians think themselves to be. Is it better that the government impose one idea of what's right - in this case, school choice - on all children? It cuts both ways.

Well, actually, it doesn't cut at all.

P.S. - Why all these references to Darwin? The debate isn't about Darwin, it's about evolution. Darwin was a man; evolution is a set of ideas. Darwin contributed many of those ideas, but the only reason I can think of to frame the debate as about him is that you don't want to engage the actual ideas.

Friday, August 04, 2006

Maybe my job isn't so bad after all

Since when did the government stop giving teachers (albeit loosely-defined) lesson plans? That's what NCLB and district curriculum standards are all about, Charlie Brown. At my job right now I'm the process of proofreading thirty teacher-written essays about leadership, nearly all of which touch upon the conflict between educators' desire to create new and presumably more effective and creative curricula and the government's insistence that students learn a prescribed set of skills. Obviously this conflict originates more from the state's testing requirements than content requirements, but the two are tightly linked. The problem isn't the state's lack of guidance but their failure to provide it in a useful way.

I don't think any one of your three hypotheses is correct. First, it's not the public's (i.e., the state's) obligation or business to create specific curricula or lesson plans. The government isn't famous for being good at specialization. That's what experts, usually in the academic or private sectors, are for. (As the benefactors of public education, however, the state is entitled to create minimum educational requirements akin to AYPs, provided that, unlike AYPs, they are developed by and for educators and not to sate an uninformed public who has been falsely convinced that teachers aren't doing their job; and provided that, also unlike AYPs, the state provides schools the resources necessary to meet those requirements.)

Second, teachers as a group aren't more likely to be want to be independent than the general public. In fact, in my experience, they're more likely to work collaboratively with their colleagues across sites than, for example, computer programmers (probably because lesson plans aren't proprietary [yet], whereas software is). Teachers LOVE to share and collaborate, even if they can be defensive about their time-tested techniques.

Third, along the lines of my first argument, we should be wary of the government dictating lesson plans. When you refer to the push for teachers to be more autonomous, who is doing the pushing? The state? If teachers are feeling alienated, it's probably because of and not in spite of government dictation of education.

I think the lack of widely-utilized lesson plans is more logistical than deliberate. For one, there aren't many national or regional networks of teachers who can work collaboratively to share ideas and classroom tools. Teachers are notoriously slow to adopt new technology, and many haven't picked up on the idea of chat rooms or blogs where they could formally or informally exchange lesson plans.

Further, many teachers probably believe—with good reason—that one teacher's lessons won't directly apply to her classroom. Demographics, geography, rural v. urban setting, gifted v. special needs students ... any of these factors might render a generic lesson plan useless or unadaptable. It's natural to think, "That plan worked for Miss Brown's class, but all her students' parents are upper middle class, and my audience is working class." We lack a wide-spread networking system that connects teachers of similar backgrounds together, so inter-professional commiseration is hard to find.

Lastly, what constitutes good pedagogy is always changing. More research yields more (and presumably better) ideas, so lesson plans (like software) quickly become outdated and appear naïve to future users. Certainly some principles transcend generations, but there's an understandable desire to always have the newest (read: best) information.

If the problem is logistical, so must be the solution. My employer, the National Writing Project, is just one of the aforementioned national networks that acts as a community wherein teachers can exchange ideas and lesson plans. NWP focuses on both providing the technological infrastructure for this exchange and on encouraging teachers to utilize this technology. They connect teachers with similar geographic and demographic constituencies through national and regional programs. Their teachers-teaching-teachers model makes would-be defensive educators receptive to new ideas because their instructors are peers, not distant legislators. But NWP is just one little group, and, while they are federally-funded, the government's NCLB standards make NWP's job as difficult as humanly possible. (Oddly enough, in spite of NWP teachers' tendency to dismiss the value of NCLB, NWP-influenced students do better on state-mandated testing.)

If the NWP model could be replicated on a larger scale, if it could be not just endorsed but facilitated by the state, then indeed the government could remedy this continual reinventing of the wheel. Rather than enlist bumbling and uniformed U.S. senators to do the job, though, the structure and content would have to be generated by teachers themselves. If the state could magically replicate the ease and resourcefulness of a private company—to harness the brilliance of that teacher who sold her lesson plans on teacherspayteachers.com—rather than futz and stall the way governments like to do, we might have a pretty amazing system on our hands.

And yes, for the record, a raging liberal did just suggest that the government try harder to emulate the private sector. Ha!

Death Values

I was brought to this by thinking about the Israel/Lebanon conflict. Most Israel/Palestine/Lebanon talks I've encountered focus on who is RIGHT. And that leads to a wealth of issues -- ancient rights to the land, territorial aggression, long-term considerations like birth rate & availability of weapons, broader regional concerns, the morality of technological imbalance.

I can't sort it all out. Nor can you. That can lead to one of two conclusions, I think. The first is that you base the RIGHTNESS of a conflict on a heuristic of incomplete information and news reports. There's nothing wrong with this, we do it with everything.

But the other is that you don't care about, in close calls, who has the absolute rightness of the situation. I call this the Football Side. Now, I have family in Israel, soon. My Fiancee has an Israeli father. And I have a lot more in common with Israel's western, modern culture then anything in Palestine or Lebanon. So while it's not quite 'My Country, Right or Wrong,' it's certainly 'Israel until undeniably proven otherwise.'

And even should Israel mess up horribly, chances are I'll still see the issue from Israel's side -- as a failure among the political/military elite, rather then an indictment of the country. Just as I would see something similar in America, viz Guantanamo.

This being the case, is it inevitable that I'm valuing Israeli lives more highly then Lebanese lives? And if so, is that morally respectable?

Even if we don't have enough information -- if we ever could! -- to judge the rightness of a situation, we do have body counts. If I'm not bothering to figure out who is right, I can at least count corpses. Regardless, I am on Israel's side. And, honestly, I feel it more strongly when someone is killed in Tiberias, where I've been, then when distant Lebanese are killed. Is this just a normal part of human experience -- no one would question it if I felt more strongly for a friend then a stranger -- or mere cultural prejudice, a demonstration of bigotry based on nothing more then national borders?

Buying the Wheel

As a young teacher, Kristen Bowers toiled night after night, struggling to grade tests and come up with innovative teaching materials for her English courses at South Hills High School in West Covina.

"I remember thinking, 'Can somebody just invent something so I can have a life?' " said the 32-year old San Dimas resident.

...

Since posting her guides on TeachersPayTeachers.com, a new, EBay-like website that allows educators to post their work online, Bowers has seen her course materials fly off the site.

Indeed, my impression has always been that teachers have to - or, at least, good teachers will - dedicate altogether too much time to making sure they've got good plans for the next day's lessons. And while my experience is also that teachers tend to like to control their own curriculum - there are a lot of Type A personalities in the field of education - there seems to be an enormous potential for increased efficiency here.

I've always found it totally appalling to see teachers designing curriculum from scratch, since the implication of that activity must be that either 1) in decades and decades of teaching, really good curriculum has yet to be developed for a particular purpose or 2) there's really good curriculum out there, but teachers don't know how to acquire it. I mean, sure, teachers will always want an element of flexibility - but are we really so hard-pressed for educational resources that we often have to start from the ground floor?

This being a political site, my political question is this: is the state of affairs that this new online store for lesson plans aims to rectify the result of public failure to devote adequate resources to supporting teachers, or is it that teachers, as a rule, just prefer to make up their own lesson plans? Or, a third option I can think of - is a lack of widely utilized lesson plans an unintended consequence of pushes for increased teacher autonomy? Are we just too wary of the government getting involved in our classrooms?

weird formatting

Update: Fixed.

Public Financing for California

One of liberals' greatest weakness has been a the corruption and stagnation of state Democratic parties. For lack of innovation California really does stand out. Passing this prop would change the playing field in a way that would give regular citizens a greater voice and hopefully will lead to fresh-blood in the local Democratic party.CLEAN MONEY...There was some good news for California Democrats today:

Defying some of his strongest supporters in the race for governor, state Treasurer Phil Angelides on Thursday threw his support behind a November initiative that would use taxpayer money to fund campaigns and would markedly restrict political donations to candidates.

....Big corporate donors and major unions — such as the California Teachers Assn., one of Angelides' biggest backers — oppose the campaign finance overhaul.

....But [Angelides] characterized Proposition 89 as nothing less than protecting democracy and creating a system "where it's not how much money you can raise, but the power of your ideas."

"It has become a dialing-for-dollars democracy, with the unjust influence of the special interests silencing the voices of Californians," Angelides said at a rally at the nurses union headquarters in Oakland.

Arnold Schwarzenegger, unsurprisingly, opposes the measure. Too European, he says. Plus it raises taxes by 0.2%.

I don't where I have to go to volunteerer for this but wherever it is I'm going to find out.

On Forming Coalitions

...isn't the abortion debate a really weird proxy for all sorts of more fundamental debates, about the prevalence of sex ed and policy to deal with unwanted children, for instance?Indeed it is. Here are a couple possible explanations:

- The anti-abortion movement is a diverse coalition of groups. Large subsets may have homogenous views on the “prevalence of sex ed” or “policy to deal with unwanted children” but they have decided to focus on their common goal first.

- The anti-abortion movement really isn’t all that diverse. They actually do push for those other issues, but they get the most attention for abortion.

- The anti-abortion movement isn’t diverse and they aren’t really pushing hard for those other things because it’ll upset the conservative political coalition.

I guess what I’m saying is that “shallow” support is important to an interest group. Or failing that, an interest group at least needs to be “respectable”. If it isn’t it won’t be able to form coalitions and it will find itself shut out from power. Example: The number of people who actively oppose building a wind-farm of Nantucket Sound is probably smaller than the number of Neo-Nazis in this country. But one is a respectable position (even if I happen to disagree) the other is not. I’ll happily accept and work with an anti-Wind-Farmer Democrat but I wouldn’t ever attend the same meetings as a Neo-Nazi or work with one for a common goal*.

That’s really I think one of the key ways in which the battle for “hearts-and-minds” translates into winning elections. Few hard-core supporters ever actually change their minds. The best you can manage is to convince everyone to stop politley ignoring the issue.

*Except maybe ridding the world of alien invaders from outer space… first things first.

Thursday, August 03, 2006

In which I (Partially) Agree with PZ Myers

Myers wants to "dash some cold water on any sense of triumphalism on the pro-science side" that might result from creationists losing their majority on the Kansas State Board of Education. Myers says:

Elections and courts are stop-gaps. They are ways to temporarily block trends from becoming entrenched in our social institutions, but as I tell everyone, all we have to do is lose one and we're screwed. We are on the losing side as long as our response consists of throwing up more and more sandbags in the face of a rising flood—we need to get to the source of our problems and work there, and if we put all our efforts into these legalisms and desperately close elections, we're being distracted from the work that's really essential.But then Myers conspicuously fails to describe what, exactly, the "really essential" work is, except to say that

[I]n the long term, the elections don't matter. What counts are the thoughts of 15 year old kids right now, and how their minds are being shaped, and I guarantee you that there are damn few of them who even knew there was a school board election going on. What are they reading? What are they being taught in school? What are their parents telling them, and what will they tell their kids 10-20 years from now? How will they vote when they're franchised in a few years?My concern here is that when you say that the important thing isn't political victory, but winning over hearts and minds, it's easy to forget that political victories are good ways to win over hearts and minds. After all, how do you convince the 15-year-olds of today to reject bad science in the future if not by teaching them to embrace sound science now? And how do you teach them sound science now? One of the first steps I can think of is to make sure that people who appreciate sound science are the ones making decisions about large-scale education policy.

It's absolutely true, of course, that people's beliefs and convictions influence the way they impact public policy, but the causation works in both directions.

My guess is that there's some tendency to think of politics as somehow inherently cynical or dirty; the worlds of ideas or hands-on intervention are more admirable because they're closer to being "really essential". That's a topic for another post, maybe.

Update: At the Panda's Thumb, Reed Cartwright has an example of what I mean.

You tell me the morning after

But why do I find that incessant debate so pointless and boring to begin with? I realized that it's not the content of the controversy that puts me to sleep; in fact, considering the legal relationship between the state, women, and their fetuses is fanscinating. Rather, what bores me to tears about the abortion debate is that the prevailing arguments used on either side are so rhetorically useless.

None of the names assigned by a side's opponents-- pro-abortion, anti-choice, and so on--is actually true, and none of the self-assigned terms--pro-life, pro-choice, and so on--is unique to that side.

Honestly, do "pro-abortion" supporters actually round up women, put them on a shuttle to the nearest Planned Parenthood, and encourage them to get abortions? Do members of the "anti-choice" camp intervene when someone is waffling between a latte and a mocha, insisting that she isn't allowed to choose? Alternately, since when do "pro-lifers" have the monopoly on thinking that death is a bad thing? I'm obligated, of course, to bring up the irony of how the "pro-life" constituency usually also supports war the death penalty, and vice versa.

When pro-choicers accuse their adversaries of being universally sexist and ignorant of basic scientific fact, do they really mean that? More ridiculously, when pro-lifers claim that "abortionists" (as if it were an ideology) are murderers with no regard for human life, have they bothered to look up "murder" first? Why are phrases like "unborn child," which is oxymoronic, even allowed into the debate?

This disregard for semantic accuracy is as effective as calling George W. Bush a terrorist. Yes, we get it; W. is a horrible human being. But he's not literally a terrorist, and calling him one accomplishes nothing.

Making exaggerated claims with overblown or inaccurate terminology clouds the real argument about the legal and ethical grounds that need to be considered when granting women access to abortion. It's much easier, of course, to call Planned Parenthood a Nazi-like death machine than to actually argue about why fetuses should be granted certain legal protections. But it doesn't get us anywhere. I'm more swayed by science and rhetoric than picket signs and name-calling.

Science is especially important when considering drugs like Plan B. Knowing exactly what emergency contraceptives do and being able to clearly identify why your do or do not oppose these medical processes makes arguments on the topic so much more productive and interesting.

This could be my bias as a coathanger-weilding pro-abortionist, but I think the pro-life side has a larger arsenal of meaningless phrases and groundless invective than does the pro-choice side.

Blogging is stupid (but journalism can be stupid too)

Even if the vast majority of blogging output is as stupid as mine a valuable watch-dog function is being added to public discourse that wasn't there before.Jay Rosen might say that all four of these--Beinart, Abramowitz, Harris, and Ricks--believe that they are performing in front of an audience rather than participating in a conversation. They believe that they are engaged in a one-to-many one-way transmission of information and misinformation, rather than a many-to-many conversation. Beinart and company know that what they printed was not what Renehan wrote, but don't see that as a point of vulnerability. Harris knows that there were those of us in the spring of 2005 who were disappointed that Gingrich was of no help on Mexico but elated that Gingrich's vaunted advocacy of poorly-drafted balanced-budget amendments was all show and no substance, but doesn't think it poses a problem for his story of Gingrich Ascendant. Ricks sees Washington Post readers at the end of 2003 as having no right to learn then of his judgments then that Paul Wolfowitz was a dangerous fool and that Raymond Odierno's division was losing the war, and no right to complain later that he misinformed them. And Michael Abramowitz--rolling on the floor in hapless fits of laughter is the only sane response one can have to somebody who writes that "perhaps" the "neoconservative cause" has "not been helped" by the fact that the occupation of Iraq has "not gone as smoothly" as "some have predicted."

Am I wrong in seeing a common thread here? In all four cases there seems, to me at least, to be a particular default assumption: each of the four seems to believe that he can misrepresent stuff in ways he finds convenient because nobody who knows about it--not John Renehan; not Washington Post readers in late 2003; not those who worked for, with, and against Gingrich in early 1995; not those who have even a shadow of a clue about Iraq--will be able to answer him with as big a megaphone as he has.

Netroots mind-control

Many detractors claim that Kos earns his large following through Rasputin like powers of propaganda. David brooks explains that Kos "The Keyboard Kingpin, aka Markos Moulitsas Zuniga, sits at his computer, fires up his Web site, Daily Kos, and commands his followers, who come across like squadrons of rabid lambs, to unleash their venom on those who stand in the way". Apparently Kos has some kind of mind-control device hidden in his html. But while simple propaganda can explain why a misguided youth would join Jim Jones, it's not really enough to explain why so many intelligent people appreciate "netroots".

Mark Schmitt doesn't blog much, but whenever he types it pays to listen. Here he provides an explination that doesn't rely on magic mind-control powers:

They aren't looking for the party to be more liberal on traditional dimensions. They'’re looking for it to be more of a party. They want to put issues on the table that don'’t have an interest group behind them - like Lieberman'’s support for the bankruptcy bill -- because they are part of a broader vision. And I think that'’s what blows the mind of the traditional Dems. They can handle a challenge from the left, on predictable, narrow-constituency terms. But where do these other issues come from? These are "“elitist insurgents,"” as Broder puts it - since when do they care about bankruptcy? What if all of a sudden you couldn't count on Democratic women just because you said that right things about choice - what if they started to vote on the whole range of issues that affect women's economic and personal opportunities?This explains what we are seeing in Conetticut far better than brain-wave manipulation: liberals are tired of being represented by single-issue groups which sell out all the small liberal issues for one or two big ones. And it's no wonder that an Iraq-war supporter like Aaron* would be afraid of something like this: in the world of single-issue advocacy groups a project like the Iraq-war (which has strong proponents amongst a small circle of "liberal" pundits) is a reasonably powerful interest group in the Democratic tent. In the world of liberal voter opinion on the other hand, Iraq-war supporters have just enough adherents to comfortably fit around TNR's conference table.

Now, I don't know if the netroots are going to be successful in this goal or how true to their vision they will stay. God know the movement often seems short on brain-cells and high on emotion and some of their views on political strategy really are dumb. On the other hand liberals need to admit that the single-issue organizations of the past are no longer working. A solution has to be found, even if this isn't it.

*To be fair his position is not entirely clear. I think it currently stands at "There was no right answer to the Iraq question". Certainly he's not willing to asert that invading Iraq was a mistake even in retrospect.

Wednesday, August 02, 2006

Conservative Nanny Blog

Tuesday, August 01, 2006

Compare and Contrast

Before I head back to work tomorrow for the first time since July 7th - if you don't count an I-wouldn't-call-it-working field trip to Boomers - I thought I'd do a little compare-and-contrast between the styles of our own local political character Mayor Newsom and my home state of Illinois's own unfortunately-named Governor Blagojevich.

Before I head back to work tomorrow for the first time since July 7th - if you don't count an I-wouldn't-call-it-working field trip to Boomers - I thought I'd do a little compare-and-contrast between the styles of our own local political character Mayor Newsom and my home state of Illinois's own unfortunately-named Governor Blagojevich.Today was the official unveiling of SF Connect, Gavin Newsom's expansion of the remarkably popular Homeless Connect program. The idea, very broadly, is to create a system that can encourage voluntarism and then coordinate volunteers to meet particular needs in the city of San Francisco. My thinking on this sort of micro policy is that it's a good way to get little things done at the margin, but doesn't stand much of a chance of creating the sort of sweeping changes Newsom implies it could.

But what really struck me was the controversy - not about the substance of the program, about which there appears to be little, or even about the apparent impropriety of Newsom setting up a non-profit organization to accept private donations essentially without limit. No, the controversial element I liked was this one:

Newsom's director of community development sits on the seven-member board of directors. And Newsom's picture is featured prominently on the SF Connect Web site, which also features a podcast by him.Funny line...but is there anything to the complaint? My initial reaction was "no" - Newsom's a big feature of the project because he's the mayor, right?

Kayhan, however, said SF Connect is "apolitical."

"Anytime an elected official tries to do anything innovative or that makes a big splash, it's looked upon as trying to be for his next campaign," he said. "I wouldn't have taken this job if it was driven by a campaign or politics."

One of Newsom's political rivals, Board of Supervisors President Aaron Peskin, jokingly called the mayor's volunteer program "SF Re-election Connect."

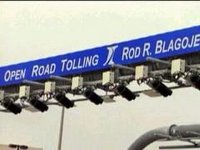

But the whole thing reminded me of a similar controversy in Illinois recently, as Governor Blagojevich seemingly tried to take all of the credit for "open-road tolling" (i.e.: being able to pay tolls with an electronic box in your car instead of stopping at a booth).

Nobody in an oversight position at the Illinois tollway or the governor's office knew about plans to spend nearly a half-million dollars on the big blue signs that advertise Gov. Rod Blagojevich's name to thousands of motorists a day on Chicago-area toll roads, the toll authority's chairman says.Now, I know what you're thinking: "How do you pronounce 'Blagojevich'?" (Answer: blah-GOY-ah-vitch) Also, you might be thinking what my dad and I thought when we looked at the signs: "Ha! Look at that! Blagojevich is pretending he invented electronic tolling!" By the same token, though, Mayor Newsom didn't exactly invent volunteering. Newsom's maybe just a little more savvy about getting himself in the spotlight.

...

The signs, the first of which were erected last year, cost the tollway $15,000 apiece, $480,000 for the total order of 32 signs. They do not provide directions, information about how open-road tolling works or how motorists can subscribe to I-PASS. The signs say in large letters: "Open Road Tolling. Rod R. Blagojevich, Governor."

So are we supposed to get all in a tizzy about elected officials linking themselves to these sorts of public initiatives? Does it depend on how they do it? Or if they're taking credit for something in a dishonest way? It probably depends on a great many things, but after some hemming and hawing, I think my initial reaction to Newsom's grandstanding holds up pretty well.

Yes, there's something shameless about taking what is really a good idea in its own right and making it about yourself. I think it's important to remember, however, that these ideas we're talking about really are good ones, and it would seem a little perverse to deny our elected officials an incentive to implement good policies. Once Blagojevich gets his name plastered over the tollways in the Chicago area, you had better believe he's got a big incentive to make sure the whole enterprise works.

So I say give the politicians their photo-ops; if they like taking credit for good ideas and solid implementation, maybe we'll get more good ideas and solid implementation.